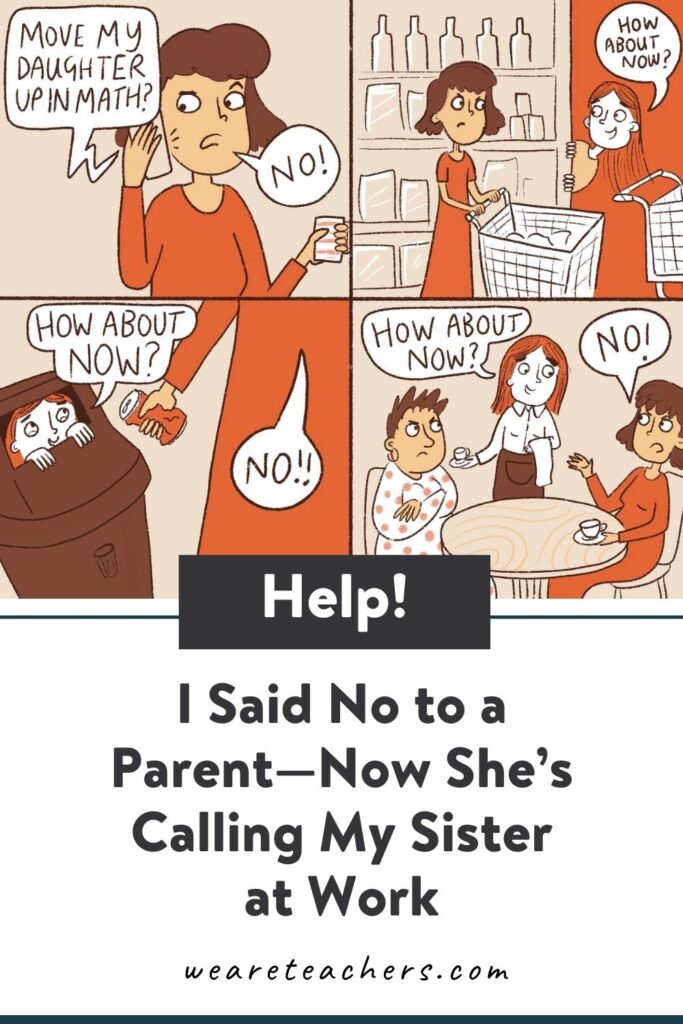

Dear We Are Teachers,

As 6th grade math teachers, my team and I decide whether to accelerate incoming 6th graders. We learned over the summer that a parent of an incoming 6th grader was very upset with our decision to not accelerate her daughter. I have her in my class, and the parent will not drop the issue. She emails me multiple times a week about this “academic injustice,” and has now moved to calling my sister at work! They have a mutual acquaintance who apparently gave her my sister’s number. This feels like such a huge overstep to me. My principal thinks she’ll lose steam, but I worry she won’t! What should I do?

—the answer is no, forever

Dear T.A.I.N.F.,

I can understand a parent’s anxiety and desperation if they feel like there’s a decision outside their control that puts their child at a disadvantage. That is understandable, even if I really don’t like this parent’s response.

That said, if parents knew the anxiety, desperation, and low self-esteem I saw children experience when parents pushed kids into classes they weren’t ready for, I feel like parents might slow their roll with this acceleration obsession.

Personally, I think your administrator should have addressed this issue long before your sister was contacted. I can’t imagine any of my former administrators not leaping out of their seats to address this nonsense.

Email your principal, “I’m embarrassed and feel unsupported that my family had to deal with an out-of-control parent. I’m requesting that you please cc me on an email in which you establish firm, clear boundaries with this parent about contacting me or my family.”

But if your administrator won’t budge, it’s up to you. This is what I’d send if my requests for an administrator to intervene went unanswered.

“I understand you would like to move [daughter] up in math. The criteria used by our acceleration committee stands. Any questions or concerns may be directed to [principal] at [principal’s email]. Additionally, my family has been advised to document any future contact with you should intervention from law enforcement become necessary.”

Is the line about law enforcement too much? Yes. Definitely.

Know what’s also too much? Calling a teacher’s sister to try to get your way. I don’t know, this lady sounds like future Dateline material to me.

When it comes to parents with serious errors in boundary judgment, I’m not here to play. 💅🏻

Dear We Are Teachers,

Every year, the senior honor society students at our high school hold a career day with booths, speakers, T-shirts, etc. The whole school gets really into it. I joined the committee for this year. During our brainstorm for ideas for speakers, I suggested having a teacher speak about a career in education. CRICKETS. Finally, a parent on the committee spoke up and said, “Yeah … we’re not doing that.” I thought other teachers would bristle at that comment or have my back, but we all just moved on to the next speaker idea. The notion that teaching isn’t a career students should consider—especially the best and brightest—really bothers me. Should I speak up about it or just let it go?

—Naive Optimist in New Orleans

Dear N.O. in N.O.,

Your feelings are totally valid. Teaching is one of the most honorable professions there is, and we should all be very worried about how few people we have who are willing to be teachers anymore.

I wonder, though, if the silence and parent’s comment were coming from a strictly “Teaching, yuck” standpoint. Maybe they were thinking:

- “Teaching is a great option, but the proximity might feel unappealing to students right now.”

- “We’d like to use our speaker times strategically to highlight careers our students have less exposure to.”

- “Teaching is a fabulous career option, but it’s no secret that teaching is really, really hard right now.”

Regardless, I think you should speak up. The honor society sponsoring the event exists because of teachers, and the committee needs to engage with the tension of why promoting education is so unthinkable. But before you do, think about some ideas for addressing possible objections.

- “Kids are around teachers all day.” Bring in teachers from international schools, highly specialized schools in a certain instructional area, professors, TikTok teachers, or other educators your students won’t have had exposure to.

- “Teaching isn’t lucrative.” Bring in a teacher making $131K in their 9th year of teaching under ImpactPlus in D.C.

- “No one wants to be a teacher.” Talk about careers in education policy and advocacy—how do we make teaching an attractive profession again?

Maybe your idea won’t fly for this year, but at the very least, get people thinking. It’s really weird to have a school committee shut down education as a career to promote.

Dear We Are Teachers,

It drives my (old-school) partner teacher crazy that I (newbie) call my third graders “friends.” She has given me all sorts of reasons why I shouldn’t, but when I’ve asked her to identify how exactly it’s harming my students, she gets flustered and can’t explain. Who is right?

—FRIEND of my friends

Dear F.O.M.F.,

Though I didn’t use “friends” when teaching, I don’t have a problem with it. Weirdly, I’m more irritated by “scholars” than I am by “friends.” Maybe I should explore that.

I don’t think you’re harming your students by calling them “friends,” but I don’t think that’s your partner teacher’s point, either. Could it be confusing to some students, especially in moments when you have to take on more of a directive or authoritative role? Sure. Is it yucky to think about teachers who might weaponize or take advantage of the “friends” thing? Yeah. But if your classroom relationships are solid and you don’t find your students confused by it (e.g. “You took away the frog I brought to school in my backpack so you’re not my friend anymore.”), I think there’s no harm in your term of endearment.

Ask your partner teacher how she feels about “scholars.” Now that’s inappropriate.*

*sarcasm

Do you have a burning question? Email us at askweareteachers@weareteachers.com.

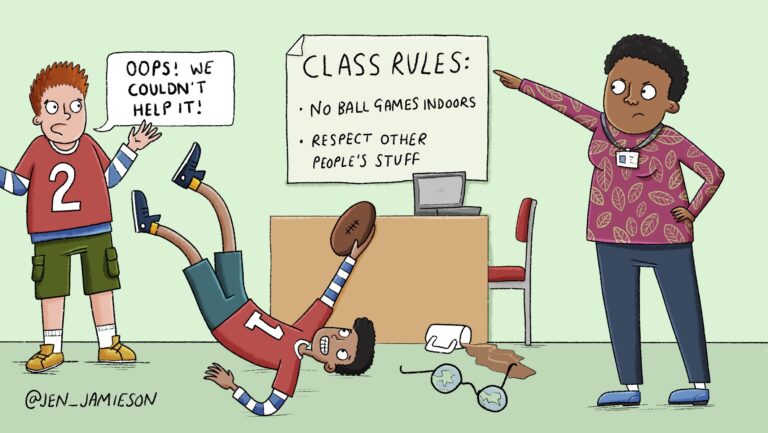

Dear We Are Teachers,

I teach high school science. Maybe a minute before the bell to leave one day, two students were playing catch with a Styrofoam sphere from a molecule unit. I told them to stop, but they didn’t. The next throw, one student dove onto my desk to catch it and shattered my glasses in the process. The parents refuse to pay because, according to them, 1. I shouldn’t have had my glasses out on my desk, 2. students shouldn’t have had time to play catch, and 3. I should have intervened more forcefully to get them to stop. The principal says that these parents are known for entitled behavior like this, but recommends I drop it and get a new pair of glasses myself. Is this a lost cause, or should I keep pressing the issue?

—BITTER AND BESPECTACLED